Food brands will now have to do away with at least one form of deceptive communication design. According to a new rule by the Food and Drug Administration, they’ll have to get rid of misleading “healthy” labels on packaging, unless the product meets criteria indicating that it actually is good for you.

The decision puts a deceptive label to rest, and offers an example of how to make packaging easier to interpret for consumers navigating the grocery aisle. Brands are supposedly all about authenticity and trust of late, but it seems sometimes the long arm of the law needs to force their hand. However, some experts say the label rule, which goes into effect on February 25, 2025, doesn’t go far enough.

An edit to legacy labeling standards

Labels are an integral part of modern food packaging, from black-and-white Nutrition Facts charts to simple symbols for recyclability and country of origin. These graphics are a bit of communication design meant to inform, but it’s not clear consumers always understand what they see.

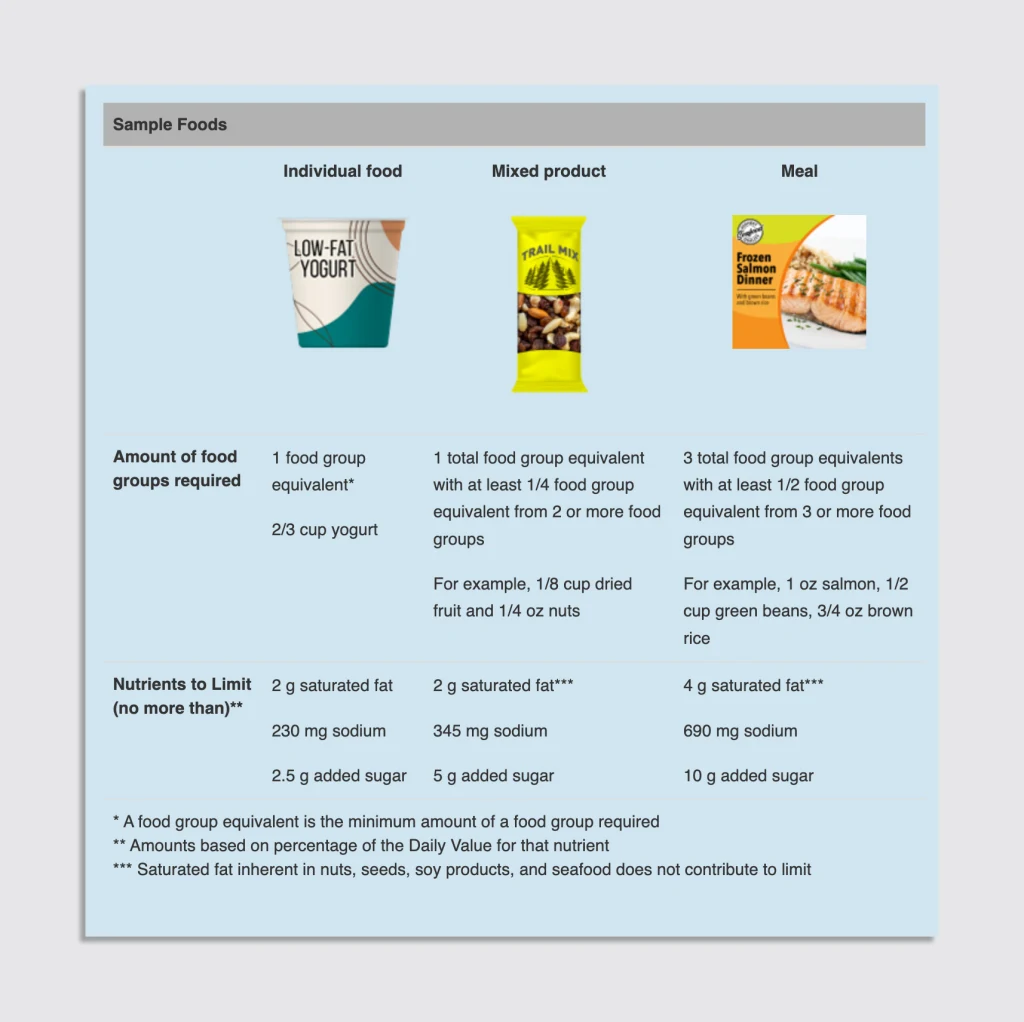

Under the new criteria, packaging can use the term “healthy” only if the product contains a certain amount of at least one of the food groups recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans—including fruits, vegetables, grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy, and protein—and doesn’t surpass limits on added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium.

These thresholds vary by food type, and it means foods like fortified white bread and many sugary yogurts and cereals that could once be classified as “healthy” can no longer be (sorry, Chobani). Additionally, the new rules automatically qualify certain nutrient-dense foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, seafood, eggs, and nuts for healthy labeling if they contain no additional ingredients except water.

The FDA is also developing a standardized “healthy” symbol that food manufacturers could use on their packaging if their products meet the criteria.

Experts say new label needs to be paired with public education to be effective

The new guidance “is a step in the right direction,” Alice Lichtenstein, a Tufts University professor of nutrition science and policy, tells Fast Company in an email, but for it to be effective, “the general public needs to be educated in its existence and how best to use it.” That’s not dissimilar to the standard for any new design system.

The new rules address the policy gap on sugary foods that were previously labeled healthy but shouldn’t have been, and accommodates for “good fats” as well as concerns about ultra-processed foods. But even these changes are “just a drop in the bucket compared to all the challenges that remain in making food labels useful for deciding if foods are healthy or not,” says Xaq Frohlich, an Auburn University history associate professor and author of From Label to Table: Regulating Food in America in the Information Age.

“Despite decades of using food labels as a policy solution to public health problems, America’s health problems persist,” Frohlich adds. “I believe this is because the FDA needs to do more than just tweak labeling rules in order to improve the nation’s food markets and the rampant misinformation in them that confuses consumers.”

The FDA says data shows a majority of Americans’ diets exceed the current recommendations for saturated fats, added sugars, and sodium, and that the dietary patterns of 79% of Americans are low in dairy, fruits, and vegetables.

Making “healthy” into a reliable, at-a-glance signal

Jim Jones, FDA deputy commissioner for human foods, sounded hopeful about the new labeling guidance, noting in a statement that the new rules may “help foster a healthier food supply if manufacturers choose to reformulate their products to meet the new definition. There’s an opportunity here for industry and others to join us in making ‘healthy’ a ubiquitous, quick signal to help people more easily build nutritious diets.”